The idea of patriotism was sharply tested within the black community during the onset of World War 1.

Many black leaders were caught between their idealistic fight for equal rights and a practical reality that dictated reluctant acceptance of second-class citizenship.

Such was the case with a proposed colored-only officer training camp.

W.E.B. DuBois, one of the nation’s leading intellectuals and radical integrationists, defended the camp as “the lesser of two evils.”

“We must continually choose between insult and injury,” he wrote in the Crisis. “We must choose then between the insult of a separate camp and … putting no black men in positions of authority.”

“Give us the camp,” he declared. “We did not make the damnable dilemma. Our enemies made that.”

It was a damnable dilemma.

These photographs offer a small glimpse of the “damnable dilemma” at the turn of the 20th Century.

On July 2, 1917, white mobs attacked the small black community in East St. Louis, Illinois after a local packing plant hired black workers. The mobs murdered as many as 300 blacks, some burned alive in their homes.

In response, less than a month later on July 28, 1917, the NAACP led more than an estimated 10,000 African Americans down Fifth Avenue in silent protest to a muted drumbeat.

“They marched,” the New York Age, a black newspaper, reported, “without uttering one word or making a single gesticulation and protested in respectful silence against the reign of mob law, segregation, ‘Jim Crowism,’ and many other indignities to which the race is unnecessarily subjected in the United States.”

Since the start of World War I, the NAACP had pressured President Woodrow Wilson to create an officers’ training school for African Americans. The result of those efforts was the Colored Officers’ Training Camp in Des Moines, Iowa.

On October 15, 1917, 639 African Americans received commissions. Although blacks comprised 13 percent of all active duty soldiers in World War 1, they were restricted to less than one percent of the total officers corps. The soldiers shown here in 1918 were part of the 88th Division, Camp Dodge in Des Moines.

During World War I, nearly 2.3 million African Americans registered to serve in the military. 367,000 were enlisted and organized to serve in segregated units. These men were leaving for training camps from Duluth, Minnesota between January and February 1918.

These soldiers shown here in France in June 1918 were among the 40,000 African American troops in the 92nd and 93rd divisions deployed in Europe during the war. Sharply opposed to black combat troops fighting side-by-side with whites, U.S. Commander John “Black Jack” Pershing Black soldiers assigned blacks to the French for combat training.

Known as the “Harlem Hellfighters,” the 369th Infantry Regiment were given a hero’s welcome when they returned to New York in March 1919.

A “Harlem Hellfighter” greeted a well-wisher during the 1919 victory parade.

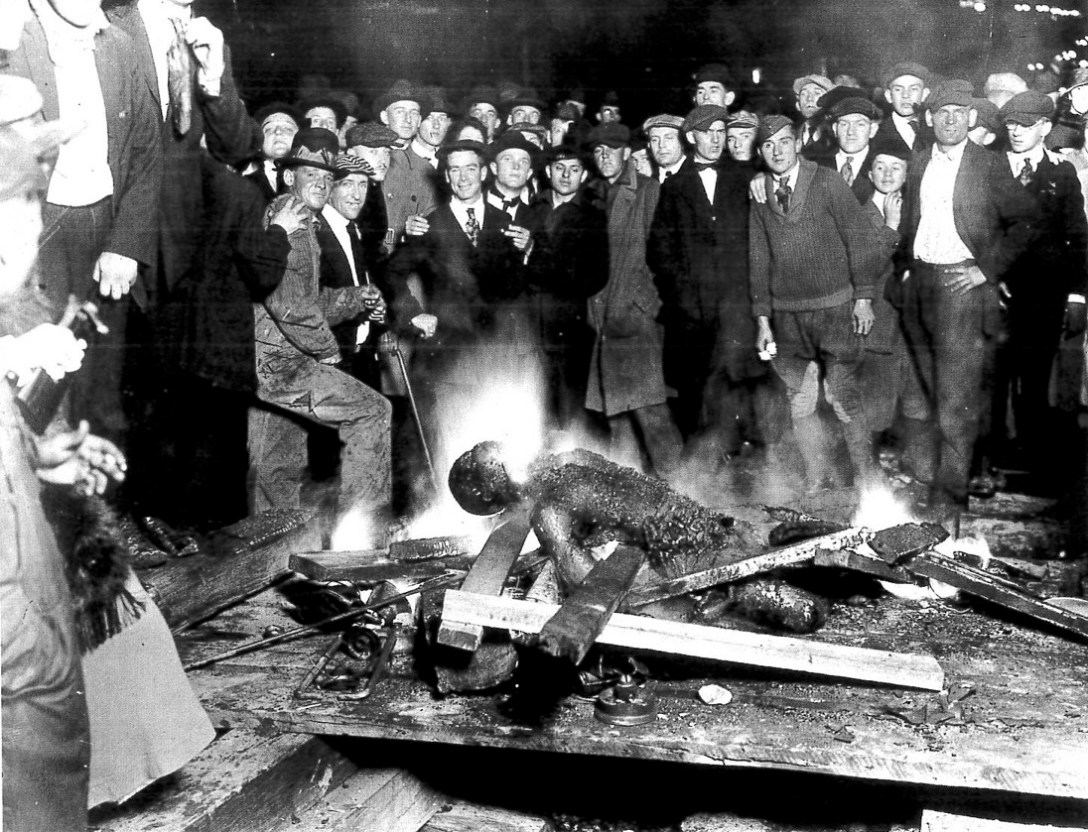

Despite “closing ranks” and fighting in Europe, African Americans still faced violent oppression at home. In the last six months of 1919 there were 25 major race riots in the United States. In this particularly gruesome lynching, a white mob of about 5,000 surrounded and attacked a county courthouse to seize a black man accused of assaulting a white woman.

The mob mutilated the man, shot him over 1,000 times, and then burned his body.

Header photo: Berean Colored Officers Club, Philadelphia, 1918. Courtesy of National Archives, Maryland.

Follow Manlyink on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and LinkedIn for more